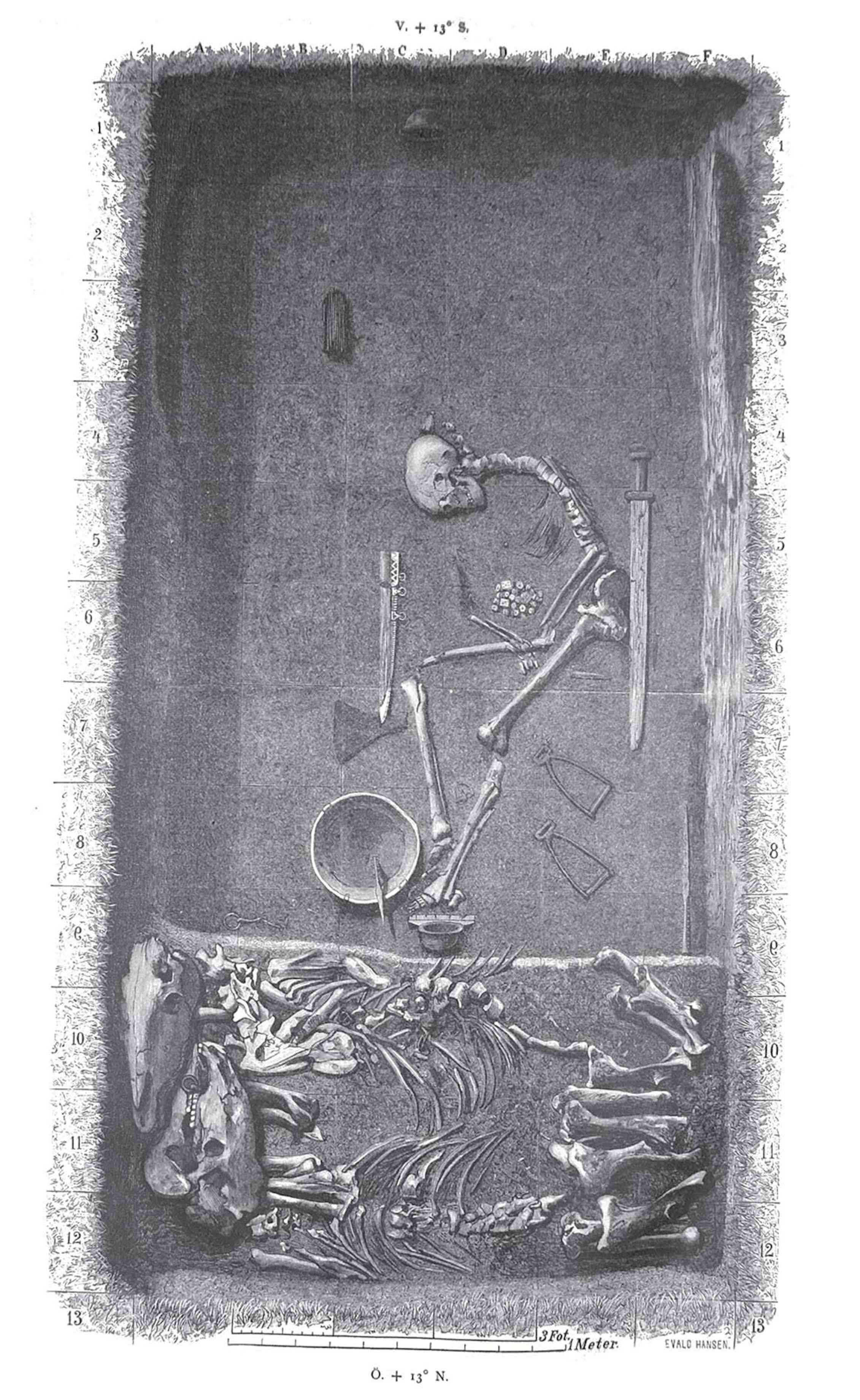

On the Swedish island of Björkö lie the remains of Birka, a significant Viking trading post. Birka is studded with burial chambers, stuffed with clues about their occupants – amber, textiles, gold, silver and many other treasures. One particular chamber caught the eye of 19th-century archaeologists, who labelled the grave Bj.581. This grave contained weapons: a sword, an axe, a spear, a battle knife, two shields and 25 arrows, and the remains of two horses.

Clearly, this was the grave of a warrior. No one really looked closely at the skeleton in this grave to confirm it was male but for 100 years, the record held that the warrior in Bj.581 was a man.

In the early 1970s, bone analysis suggested the skeleton was female. DNA analysis published in 2018 confirmed the bones were those of a woman, with two X chromosomes.

The team conducting the DNA analysis also examined the relationship between the skeleton and the contents of the grave, drawing the same conclusion as all previous investigations: “the person in Bj.581 was buried in a grave full of functional weapons and war-gear […] outside the gate of a fortress”. If it looks like a warrior, and is armed like a warrior, it must be a warrior.

Critics were unconvinced. Had the authors of the study got the wrong skeleton? Had another skeleton been mixed up in the grave? (No, the evidence is firm on both points.) In spite of these sceptics, the story of this skeleton took off around the world, precisely because it challenged so many assumptions about women, combat and the history of war.

Women have long fought in wars, but their contribution is often erased. The military historian John Keegan famously wrote in 1993 that

warfare is […] the one human activity from which women, with the most insignificant exceptions, have always and everywhere stood apart […] Women […] do not fight. They rarely fight among themselves and they never, in any military sense, fight men. If warfare is as old as history and as universal as mankind, we must now enter the supremely important limitation that it is an entirely masculine activity.

But it turns out history is full of examples of women on the frontlines: women who fought in their own right, women who dressed as men in order to fight, and women who faced great danger supporting male troops in the teeth of battle. Women have survived and even thrived as part of the machine of war – but are rarely part of military history. Why have their stories been forgotten?

A convenient amnesia

The amnesia about women in combat is a convenient, if not deliberate, forgetting. When Western governments were forced by the 1970s feminist movement to consider the question of whether women should be allowed to fight, they often pointed to the all-male battlefields of the past, even if this history was inaccurate.

Decision-makers refused to see a history in which so-called women camp “followers” were following so closely they were actually on the battlefield, providing food and drink and supporting artillery fire.

They didn’t see women in the thick of battle, fighting alongside men – most often disguised as men, occasionally in their own right, and sometimes (but rarely) even leading those men.

Women were a commonplace feature on battlefields. They also fought in sieges, which for long periods of time were far more common than pitched battles. In the Kingdom of Dahomey (now Benin), from the late 18th century, an all-female regiment of crack troops existed for 100 years.

Suppressing this history helped perpetuate the exclusion of women from combat. This, in turn, stopped them taking on military leadership roles, which required combat experience – and these roles have been a crucial route to political and societal leadership. But perhaps more importantly, excluding women from combat served as a potent reminder that despite what the feminist movement told the world, women were not equal.

Women, it was long argued, were simply too fragile to fight. They would be uniquely and horrifyingly susceptible to violence on the battlefield. And men would be too distracted by their presence to fight properly; women would disrupt the essential bond between men, between brothers, that allowed for battlefield excellence.

The exclusion of women soldiers from combat was only overturned in Australia in 2011 and in the United States in 2013. In the United Kingdom, all combat roles were finally opened to women in 2018. The exclusion of women from combat for so long was justified by a dominant view of history that presented women as having rarely demonstrated an aptitude or interest in fighting. But that history is wrong.

Read more: Why I want to serve on the front line, despite challenges for women at war

A ‘very good-looking corporal in our regiment’

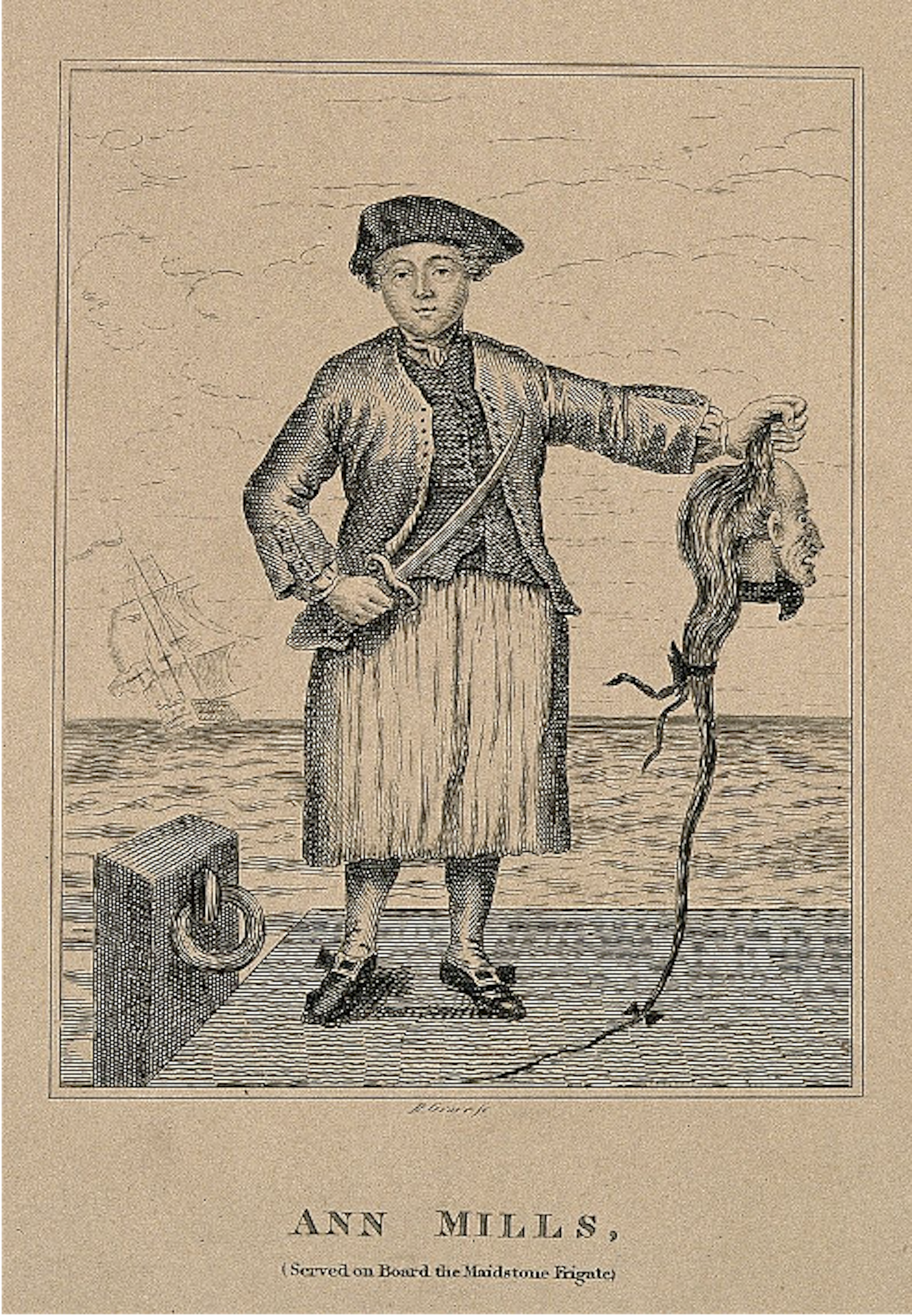

One of the most common, and intriguing, ways for women to enter combat was in male disguise. Women who dressed as men to become soldiers are known to have fought in the armies and navies of Russia, England, the Netherlands, France, various German states, and both sides of the American Civil War.

Around 119 cross-dressing women are documented as having served in Holland between 1550 and 1840; around 40 in ancien regime France; between 30 and 70 in Revolutionary France; 22 in the Prussian army during the wars against Napoleon in the early 19th century; and more than 60 in Britain between 1660 and 1832.

While these women were motivated to fight for many reasons – including safety, as life in the military was often more safe for a woman than life outside it – one of their primary motives was patriotism.

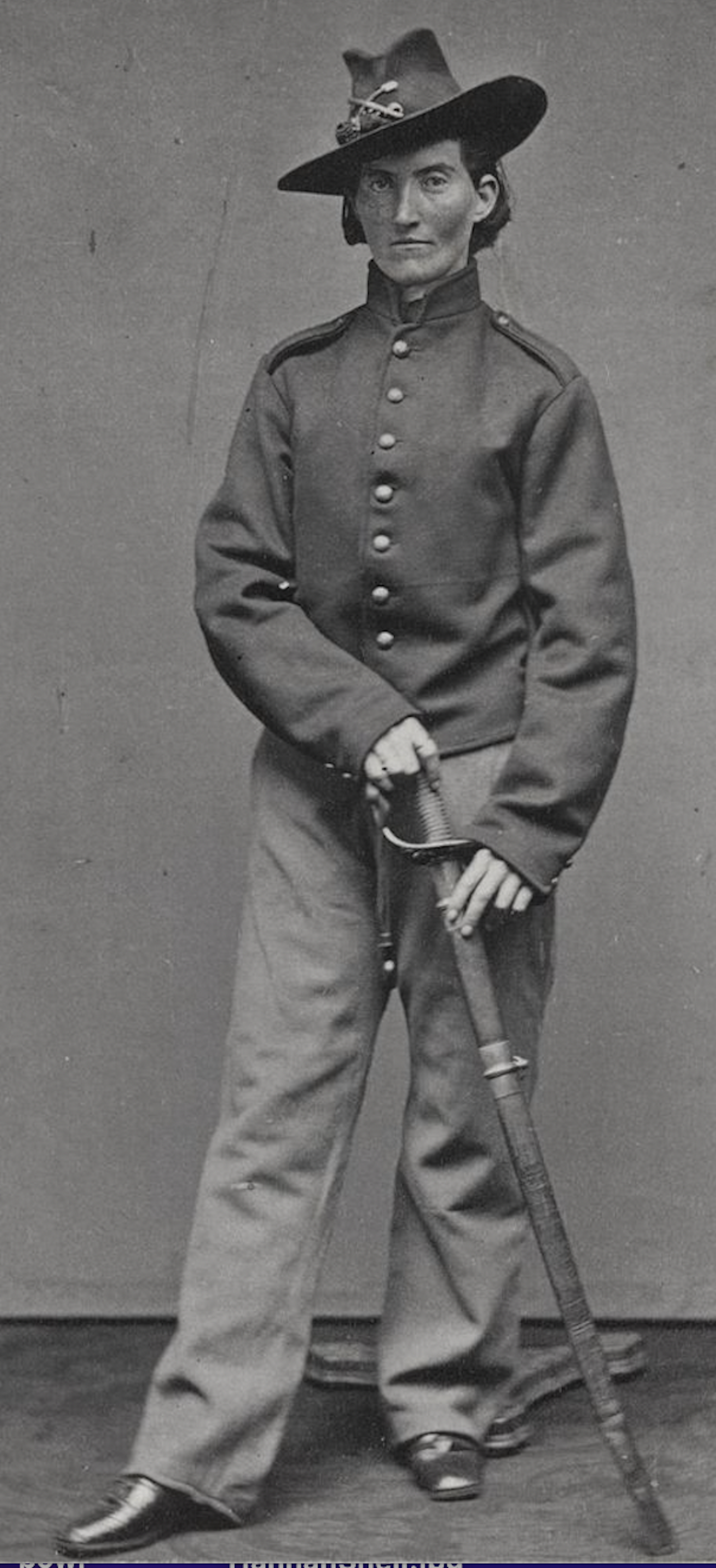

During the American Civil War, (1861–65), between 250 and 1,000 women fought. (The reason for the variation in all these numbers is that it is impossible to know how many disguised women fought – by definition we only know about the ones who were uncovered, not those whose masquerade was never challenged). There are multiple accounts of soldiers finding women’s bodies among the dead on both sides of the conflict.

One Union Soldier remarked of a Confederate soldier,

I’ve picked up a great many wounded rebs [rebels …] among these were found a female dressed in mens clothes & a cartridge box on her side […] she was shot in the breast & through the thy and was still alive &; as gritty as any reb I ever saw".

Part of the reason for the large number of disguised women during the Civil War is that all traditional forms of service for women (such as nursing or laundry) were reserved for men. The only way for a woman to join the war effort was to fight. More than 2 million men served in the Union Army and between 750,000 and a million men were in the Confederate forces over the course of the war.

Read more: Why is the Confederate flag so offensive?

Both sides were fighting a bitterly contested war with an almost insatiable need for manpower. This seems to have reduced the need for physical checks of soldiers, and as fighters were drawn from the general population, experience and skill were not the prerequisites they might otherwise have been.

One Union soldier described a new recruit encountered on a long march:

we enlisted a new recruit on the way to Eastport. The boys all took a notion to him. On examination, he proved to have a Cunt so he was discharged.

At least eight disguised women fought at the Battle of Antietam, where on the bloodiest day of the conflict, 30,000 were killed; this number may have been more, because investigations of a grave site near another battle found a female skeleton among the men. Her identity remains unknown.

Of the eight fighters at Antiteam, one woman had an arm amputated; one was shot in the neck. Another survived that battle, and the Battle of Fredericksburg, where she was promoted to sergeant only to give birth a month later.

There are confirmed accounts of five women fighting at Gettysburg. One lost her leg and two marched in the famous Confederate Army infantry assault called Pickett’s Charge. One of these anonymous women could be heard screaming in agony from her wounds on the battlefield. She would not have been alone. The Confederate Army lost more than half of the soldiers who fought that day to injury or death: 6,555 men.

Pregnancy of officers should have been a giveaway that there were disguised women in the ranks. And yet, one memo read,

The general commanding directs me to call your attention to a flagrant outrage committed in your command […] an orderly sergeant […] was to-day delivered of a baby – which is in violation of all military law and the army regulations. No such case has been known since the days of Jupiter.

Another soldier wrote to his wife, regaling her with the story of the “very good looking corporal in our regiment” who had fallen ill, before “this same good looking corporal had been relieved of a very nice little boy and that the corporal and the boy was doing first rate”.

His wife wrote back:

I think it was quite a grand thing about that corporal what a woman she must have been […] she must have been more than the common run of woman or she could never stood soldiering especially in her condition.

Women recorded their own experiences in letters home, and some were unafraid of a soldier’s life. Sarah Rosetta Wakeman (Private Lyons Wakeman) wrote to her parents about fighting and marching with a typical soldier’s bravado. “I don’t fear the rebel bullets and I don’t fear the cannon…”

After a battle, she explained, “I had to face the enemy bullets with my regiment. I was under fire about four hours and laid on the field of battle all night.”

Women soldiers in the Civil War, despite extensive documentation (and photographs), were not officially recognised by Americans later on. In fact, their existence was totally denied. In 1909, the investigative journalist Ida Tarbell wrote to the adjutant general of the US Army asking whether his department had a record of the number of women who enlisted and served in the Civil War.

Tarbell received the following reply:

I have the honour to inform you that no official record has been found in the War Department showing specifically that any woman was ever enlisted in the military service of the United States […] during the period of the civil war. It is possible, however, that there may have been a few instances of women having served as soldiers for a short time without their sex having been detected, but no record of such cases is known to exist in the official files.

The office of the adjutant-general was either lying or lazy: they did have records of women’s military service, including discharge records and pension records.

The playbook of patriarchy

Suppressing the memory of women’s combat wasn’t limited to the period after the American Civil War. The many examples of female combat during the 20th century included 800,000 to a million women who fought for the Red Army during World War II.

Yet officialdom chose to believe that women may have fought when their countries were desperate, as the Soviets were, or in rare exceptions cross-dressed as men, but as they were “exceptional”, their experiences were simply discounted.

In essence, keeping women out of combat became part of the of the playbook of patriarchy – at a time when the feminist movement was breaking down all the barriers to female employment in every other imaginable category. (The US had female astronauts in training 30 years before it allowed women in combat).

The contribution of women to warfare isn’t just important in historical terms. There is a strong link between authoritarianism and the suppression of gender equality. The right to engage in combat is no different from any other right.

Before his 2016 election, it was widely reported Donald Trump was opposed to women in combat. One study showed the two strongest factors associated with opposing the deployment of a co-ed unit into combat were support for Trump and support for the Republican Party.

Moreover, women’s demonstrated capacity in combat serves as a profound reminder of their overall social equality; it is harder to take away women’s rights if they are equal on every level with men.

Ukraine today

Today, we are sitting at the crest of a major change, whereby generations of women will move through the military with no ceiling on their progression and no rules telling them what they cannot do. The consequences of this change are already visible in places like Ukraine.

The first Russian invasion in 2014 caused Ukraine to reassess its use of women in the military. In 2018, all positions were opened to women. By 2021, there were 57,000 women in the Ukrainian military, about 22.8% (vastly exceeding most other countries). Ukrainian women were ready to fight when Russia invaded last year, and there has not been much fuss about it.

They have taken on all roles, including leadership positions. They are fighting an enemy that has resolutely kept women out of combat, despite significant recruitment issues (and a long, if now ignored, history of female combat). Ukraine is far from a perfect place for gender equality in wider society. But as it becomes normal for women to fight, and as they become heroes of the war, things may change.

Read more: Ukraine war: attitudes to women in the military are changing as thousands serve on front lines

The conflict between Ukraine and Russia also underlines the argument that authoritarian governments, whatever their diversity, have one thing in common: they suppress women’s rights. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s hyper-masculine style has relied on traditional views about gender. Domestic violence was decriminalised in Russia in 2017, and now is only punishable as a crime when the abuse is so severe it requires hospitalisation. Russian women are still barred from a list of 100 professions.

Unsurprisingly, the Russian military facing off against Ukraine has no combatant women in it – even when Putin had to forcibly conscript men to fight in 2022, he did not mobilise women. Indeed, the list of nations that admit women into combat roles remains almost exclusively a list of democracies with high levels of gender equality. Allowing women in combat roles is a key measure of gender equality.

As time goes on, in these countries at least, women will get more and more chances to demonstrate their leadership in the crucible of combat – and to bring back that leadership into society.

Sarah Percy is the author of Forgotten Warriors: a History of Women on the Front Line, published by Hachette.

I am the author of a book from which this essay is drawn but this will be clearly credited.