[ comments ]

A collection of characters, stories, and other elements

Many years ago, I did a brief stint at Google–yes, I’m an ex-Googler or Xoogler. A lot has changed since then, but even that brief exposure to Google's internal tools left a lasting impression on me. In many ways, the dev tools inside Google are the most advanced in the world. Google has been a pioneer not only in scaling their own software systems but in figuring out how to build software effectively at scale. They've dealt with issues related to codebase volume, code discoverability, organizational knowledge sharing, and multi-service deployment at a level of sophistication that most other companies have not yet reached. (For reference, see Software Engineering at Google.)

In other ways, however, Google's internal tools are awfully limited. In particular, nearly all of them are tightly coupled with Google's internal environment. Unfortunately, that means you can't take them with you when you leave.

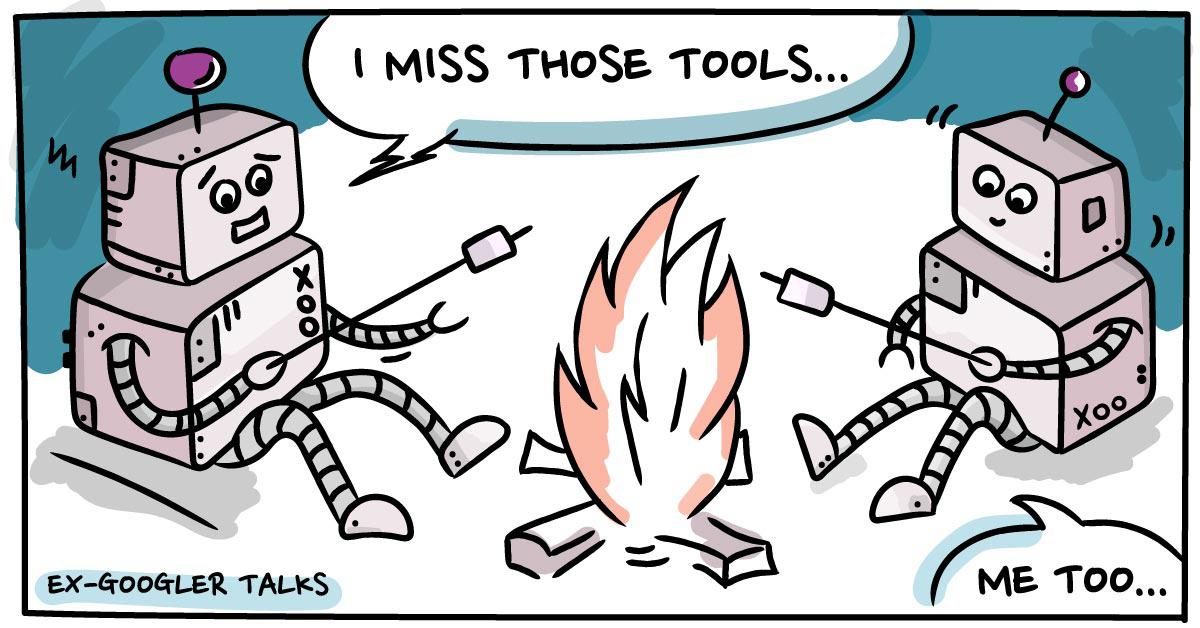

The Google diaspora has seeded so many other organizations with amazing talented people who bring lessons learned from working inside one of the world's leading technology organizations. But adapting to programming outside of Google can be tough, especially when you've come to rely on tools you no longer have at your disposal.

Over the years, I've learned from my own experience and the experience of lots of others who have left Google. Many of Sourcegraph's early customers began with an Xoogler missing code search after leaving Google. I worked closely with these people to understand the gap they were trying to fill, so that we could build Sourcegraph to meet their needs. Over time, patterns emerged in terms of how ex-Googlers sought to introduce new dev tools into their organizations, inspired by their experience with dev tools at Google. Some were successful and others were not.

I thought it would be helpful to write a guide to dev tools outside of Google for the ex-Googler, written with an eye toward pragmatism and practicality. No doubt many ex-Googlers wish they could simply clone the Google internal environment to their new company, but you can't boil the ocean. Here is my take on where you should start and a general path I think ex-Googlers can take to find the tools that will make them—and their new teams—as productive as possible

The software development lifecycle with and without Google internal tools

If you recently left Google to join another company, you probably have this overall sense of frustration that you're not as productive as you used to be. You feel you need to change something, but what is it? As a first step, you should think about what you do day to day and identify where the pain is coming from.

Both inside Google and out, the software development lifecycle looks something like this:

- You think of a feature you want to build or a bug you need to fix.

- You read a bunch of code, design docs, and ask colleagues questions. You're building an understanding of the problem and how the solution will roughly fit into the existing system.

- You start writing code. You aim first for something just working. Maybe you go back and look up docs or read some more code several times while you're doing this.

- You have it working, but you're not ready to ship. You've broken some tests, which you now fix, you add some more tests, you refactor the code to make it cleaner and easier for the next person to understand. You push it up to a branch. You wait for CI to run and maybe you implement a couple of additional fixes and small improvements.

- You submit the patch for review. Your teammates leave some comments. You make the changes. Maybe there are a few rounds of back-and-forth before the reviewer(s) approve the change.

- You merge the patch and it gets deployed.

- Monitoring systems that are in place will determine if there are any production issues. If it's your patch that caused an outage, you're on the hook for fixing it.

At every stage in this process, there is typically a tool that anchors the developer experience. Tools shape your work cycle and have an immense impact on your productivity.

| Software development stage | Inside Google | Outside Google |

|---|---|---|

| Identify feature or bug | Issue Tracker | GitHub issues, Jira |

| Write code | Critique, IntelliJ, Emacs, Vim, VS Code | Everything except Critique |

| Test code | Blaze | A bit of the Wild West, but Bazel is gaining traction |

To improve your productivity, you need to find better tools. There's a useful GitHub repository that identifies nearly every single tool inside Google and its closest comparables outside of Google: https://github.com/jhuangtw/xg2xg. This list is comprehensive, but a bit overwhelming. So where do you start?

First month: no new tools, just learn the existing ones

In your first month, don't try to change anything. Just listen and learn the ropes.

As a new member of the team, you likely don't have the influence or authority to change all the tools your team uses. Moreover, you also lack knowledge—knowledge of how and why your new team behaves the way it does and why it uses its current set of tools. Simply copy-pasting Google internal tools is not necessarily going to work for your new team. So learn what is working for your new team along with what isn't.

Low-hanging fruit

I believe that code search is usually a great tool to start with. Yes, I am the cofounder of a code search company, so of course I would say that, but here are my reasons—if these don't resonate with you, then I recommend skipping to the next section!

- It's one of the tools ex-Googlers usually miss the most from their everyday lives.

- You can try different code search engines on your own and validate that one is good before sharing it with others. This means you don't need to obtain approval from gatekeepers or expend precious social capital convincing others to try a tool you haven't started using yourself.

- It won't require forcing others to change existing habits, because your new team doesn't yet have a code search tool. If they do, then it's either bad and they don't use it much, or it's good and you already have good code search, so skip this section!

If your new company has more than a few teams in the organization, you're likely dealing with more code that you can reasonably grok as an individual person. And even if you're working in a much smaller company, chances are you're pulling in a ton of open-source code through your dependencies. This is all code that you will need to dive into at some point, when building a new feature or tracing the source of some critical bug.

Given the scale of code that nearly every developer has to deal with these days, it's no wonder that the lack of code search can quickly slow your development velocity to a crawl.

When evaluating code search engines, there are a few things to consider:

- Query language: Regular expressions are table stakes. You want to ensure the code search query language is both expressive and easy to use. Literal searches should be intuitive, and more advanced pattern matching should be available.

- Scale: Ensure the code search engine scales to the size of your codebase. If your codebase is more than a few gigabytes, a key thing to look for is whether the code search engine uses a trigram index https://swtch.com/~rsc/regexp/regexp4.html, because this is how you get regular expression matching working at the scale of a large codebase.

- Code browsing: As a user of Google Code Search, you know that search is only half the story. Once you click through to a result, you want to be able to click around to jump to definitions and find references as easily as if you had checked out the code and set up the dev environment in your IDE. * Without great code browsing, you'll be context-switching between your editor and code search engine frequently.

- Permissions: If your company enforces codebase permissions, you should consider whether your code search engine respects those.

- Overall cost: Consider both the price of the code search engine and the maintenance overhead of keeping the tool online.

Here are the common code search engines we've seen in use:

- OpenGrok: a fairly old but persistent code search engine now maintained by Oracle

- Hound: a code search engine created and open-sourced by engineers at Etsy

- Livegrep: a code search engine created by Nelson Elhage at Stripe

- And of course, Sourcegraph

Get good monitoring

Another good early area to target is monitoring. Every engineer at some point has to deal with a production issue. Production is a very different place than development—you can't just set a breakpoint or add a printf and see the effect in seconds. Making updates to production is expensive along multiple dimensions: compute resources, developer time, and worst of all, pain to your users and customers.

Deployment has changed a lot in the past 5-10 years. Microservices, Kubernetes, moving to the Cloud—these are big shifts in how companies deploy software. Many companies have adopted these new paradigms and technologies, but they have not yet updated their monitoring infrastructure to make debugging in these new production environments easy.

Fortunately, there have been some great new open-source tools and companies in recent years that have vastly improved the state of monitoring and observability in the world outside of Google.

- Prometheus is a time-series metrics tracker and visualizer that's similar to Borgmon. It lets you instrument your application to track metrics like CPU utilization, error rate, and p90 latency that change over time.

- Grafana is a dashboarding tool similar to Viceroy. A common situation is to connect Grafana with Prometheus, so you can construct a single-page view of a bunch of key metrics that indicate overall application health.

- Google pioneered distributed tracing, an essential tool for increasingly common multi-service architectures, with Dapper. One of the creators of Dapper, Ben Sigelman, went on to start Lightstep. Distributed tracing is now a feature of many monitoring systems, including paid offerings like Honeycomb and Sentry and open-source projects like Jaeger, built by Uber engineers.

Monitoring is a bit trickier to introduce than code search, since it has to be integrated into the production environment. This often involves changing the deployment environment, which probably means persuading the team that controls the deployment environment. It may also entail adding instrumentation code, which involves submitting patches to the various teams that own the code being instrumented. However, it is still easy in the sense that introducing a new tool doesn't require anyone to change existing habits. People are free to use the new tool or not, which eliminates a strong source of objections when you're trying to get the tool first deployed.

After you're in good standing: code review

Introducing code search and monitoring doesn't require asking anyone on the team to change existing workflows. Changing the code review tool, however, does.

Chances are that if you'd been at Google for awhile, the way that code review is done outside of Google has struck you as a little weird. GitHub Pull Requests is the most common code review tool, but ex-Googlers usually have a few complaints about it:

- It is not straightforward and sometimes not possible to view changes made since the last round of reviews. The easy path only lets you review the entire outstanding diff.

- There is no support for stacked CRs.

- The entire diff across all files in the changeset is displayed as one giant page, and it's hard to keep track of what hunks you've reviewed.

- GitHub PRs are very unopinionated about how reviews should be done. Without adding additional third-party integrations, the review process can seem loosey-goosey, and even with third-party integrations, it still may lack the ability to enforce finer grained review and sign-off policies.

- There is limited fuzzy jump-to-def or find-references for certain languages, but it is nowhere near the level that Critique supports inside of Google.

The closest thing to Critique you can get outside of Google is Gerrit. Gerrit began life as a fork of Rietveld, which itself was an open-source fork of Google's original code review tool, Mondrian. It should therefore feel very familiar, as it descends from a line of tools that were created to support the exact way that Google does code review.

Phabricator is another code review tool that ex-Googlers often prefer to GitHub Pull Requests. Phabricator began life as Facebook's internal code review tool and was subsequently open-sourced and released to the outside world. There's also a company behind it, Phacility, that offers hosted instances and support, in case you don't want to be on the hook for maintaining your own instance.

Another tool worth looking into is Reviewable, created by ex-Googler Piotr Kaminski. Unlike Gerrit or Phabricator, it is cloud-only, but may offer the code review experience that's closest to what is done inside Google today.

When selling the benefits of Gerrit, Phabricator, or Reviewable to the rest of your team, it's important to identify the existing pains the team is feeling with their existing code review tool. Here are how some common pain points are addressed by switching from a GitHub-Pull-Request-like tool to a Gerrit-like tool:

- Gerrit facilitates a more structured review process, with explicit sign-offs, which can be good if you've grown the team and want to enforce stricter review policies across the organization.

- Gerrit makes reviewing larger diffs easier, because you can go file by file, view changes since the last round of review, and stack CRs. This enables faster, more thorough reviews.

Gerrit, Phabricator, and Reviewable let you closely approximate the general review flow that you had inside of Google, but one thing that neither provides is code intelligence. If you're missing code intelligence in your current code review tool or find the GitHub PR code intelligence lacking, try the Sourcegraph browser extension. This connects to a Sourcegraph instance to provide tooltips, jump-to-def, and cross references during code review. It works with GitHub PRs, GitLab MRs, Phabricator, and Bitbucket Server. Support for Gerrit is on the way.

When you're ready to slay the dragon

The most intractable part of the software development life cycle is often CI and the build system. This is because understanding the build often involves understanding every piece of the overall codebase in a fairly nuanced way. Speeding up the build is something that various people try to do over time, and so the build code accrues a growing set of hacks and optimizations until the point is reached where the number of people who actually understand enough about what is going on to make a change with zero negative consequences is very small.

In short, the build system is often a big giant hairball, and one that you should be wary of trying to disentangle before you pick off the lower hanging developer productivity fruit. It may be tempting to tackle this earlier, because Blaze was worlds better than what you're using now and Google has even helpfully open-sourced a derivative of Blaze called Bazel. But Bazel is not Blaze—for one, it lacks a massive distributed build cluster that comes free alongside it—and the world outside of Google is not Google.

Bazel is not a silver bullet. When Bazel was first released, many open-source projects in the Go community switched to using it in favor of the standard Go build tool. However, within a year, many of these switched back due to complexity of use, unfamiliarity in the rest of the Go community, and the fact that builds seemed to actually be slower with Bazel. Since then, there have been major improvements to Bazel's support for Go, but you need to rigorously evaluate what improvements you'll see if you switch over to it.

In order to do this rigorous evaluation, you'll want to have plenty of other great dev tools already in place. In particular, you'll want to have great code search, so you can actually dive into the build scripts in various parts of the codebase and understand their ins and outs. You'll also want to have a great code review tool in place, because changing the build system is going to be a complex change that requires approval from many different engineering teams.

Once you're ready to slay the dragon, you should understand there are a number of build tools in addition to Bazel that are designed to enable scalable builds in large codebases. These include:

- Buck, from Facebook

- Gradle, popular in the Java world

- Pants, created by an ex-Googler originally for Twitter and Foursquare

- Please, a newish build tool created by ex-Googlers, heavily inspired by Blaze

There's also YourBase, which is not a build tool, but a CI service started by ex-Googler Yves Junqueira to bring super-fast and scalable builds to the world outside of Google, independent of what underlying build tool is used.

Operating like a Xoogler

Google prioritizes developer experience and developer tools in a way unlike most other companies. Googlers and ex-Googlers have the benefit of firsthand experience of using first-class dev tools that add a huge amount of leverage to their natural talents and abilities.

One of your competitive advantages after leaving Google will be to apply these experiences to bring great new dev tools into your new organization to boost your own productivity and the productivity of your teammates. By using these tools to spread effective best practices for developing software at scale, you can bring one of Google's key competitive advantages—the effectiveness of its engineering organization—to your new company.

Building software at scale is hard. As everyone who has read The Mythical Man Month knows, you can't get better software just by hiring more engineers. You need better tools. Just as software is a multiplier for the productivity of end users, dev tools are a multiplier for the productivity of the people who build the software. So if you truly believe in your new company's mission, make it one of your priorities to use your special knowledge as an ex-Googler and bring them the best developer tools available.

Try out Sourcegraph. Get started searching your code by self-hosting Sourcegraph – free up to 10 users. Or try Sourcegraph Cloud to easily search public, open source code.

Please feel free to ask us questions either via posting on Twitter@sourcegraph or sending an email to hi@sourcegraph.com.

About the author

Beyang Liu is the CTO and co-founder of Sourcegraph. Beyang studied Computer Science at Stanford, where he published research in probabilistic graphical models and computer vision at the Stanford AI Lab. You can chat with Beyang on Twitter @beyang or our community Discord.

More posts like this

Try Sourcegraph for free today

You'll be searching your own code in 10 minutes. You can run it self-hosted (all of your code stays local and secure).

[ comments ]